An international partnership between the Associação Cultural Videobrasil and

Videobrasil. Needs No Translation. Four Decades of Video and Performance

- Date:

- 12 Dec 2024–

9 Feb 2025

- Age restrictions

- 16+

Cao Guimarães, Rivane Neuenschwander, Diana Kapizova, Eder Santos, Eletroagentes and Alfredo Nagib, Gia Rigvava, La Decanatura, Lyudmila Gorlova, Sandra Kogut, Viktor Alimpiev, Walter Silveira, Pedro Vieira, TVDO, Wagner Morales

The first Videobrasil Festival was held in São Paulo in 1983. It was a showcase of young art in a country that was increasingly confident of its place on the cultural map of the world. From the outset, Videobrasil gave a special place to artists and filmmakers from the so-called Global South. A new era was dawning as alternative geopolitical poles emerged to replace the old division of the world into socialist and capitalist camps. The Festival has always been most interested in those places on the world map—South-East Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe—where life changes rapidly, as it does in Latin America. Over time, this interest has led to the emergence of a major institution, Associação Cultural Videobrasil, which is dedicated to the display, archiving, popularisation, and research of non-conventional forms of screen culture.

The exhibition Videobrasil. Needs No Translation marks key milestones in the development of video art through works presented in the Festival programme over the years and today preserved in the Videobrasil Historical Archive. This multi-layered narrative, consisting of four chronological sections, brings together the themes and techniques that artists have employed to respond to key events of the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries. The authors explore the different languages of video and their relationship to performance, engaging in dialogue with the cinematic traditions of different countries and focusing particularly on local narratives—the traumatic experiences of the colonial past and the consequences of socio-political cataclysms that have shaped the identity of the Global South today.

The exhibition showcases the diversity of the formal experiments that have been made possible by developments in technology, from the proliferation of home video cameras, cable television, and clip art in the 1980s and 1990s to the widespread use of computer graphics, image generation, and virtual reality in the last two decades.

At the centre of the story are works that combine the expressive means of video with body language and performative practices. They add up to a universal hybrid format that exists beyond the boundaries of states and natural languages and thus does not require translation. The exhibition includes documentation of a broad range of artworks that reinterpret the devices of public performance that have shaped the specific language of mass media, and that explore the phenomenon of performativity itself—the theatricalisation of digital life.

In different years, the Videobrasil Festival programme has included works by several Russian authors. Some of these are woven into the history of the Festival and included in the exhibition along with works from other countries. However, a Russian thread is singled out and highlighted. Some of the videos from Russia rhyme with the main narrative, others are emblematic of their time or resonate with works from the Videobrasil Historical Archive.

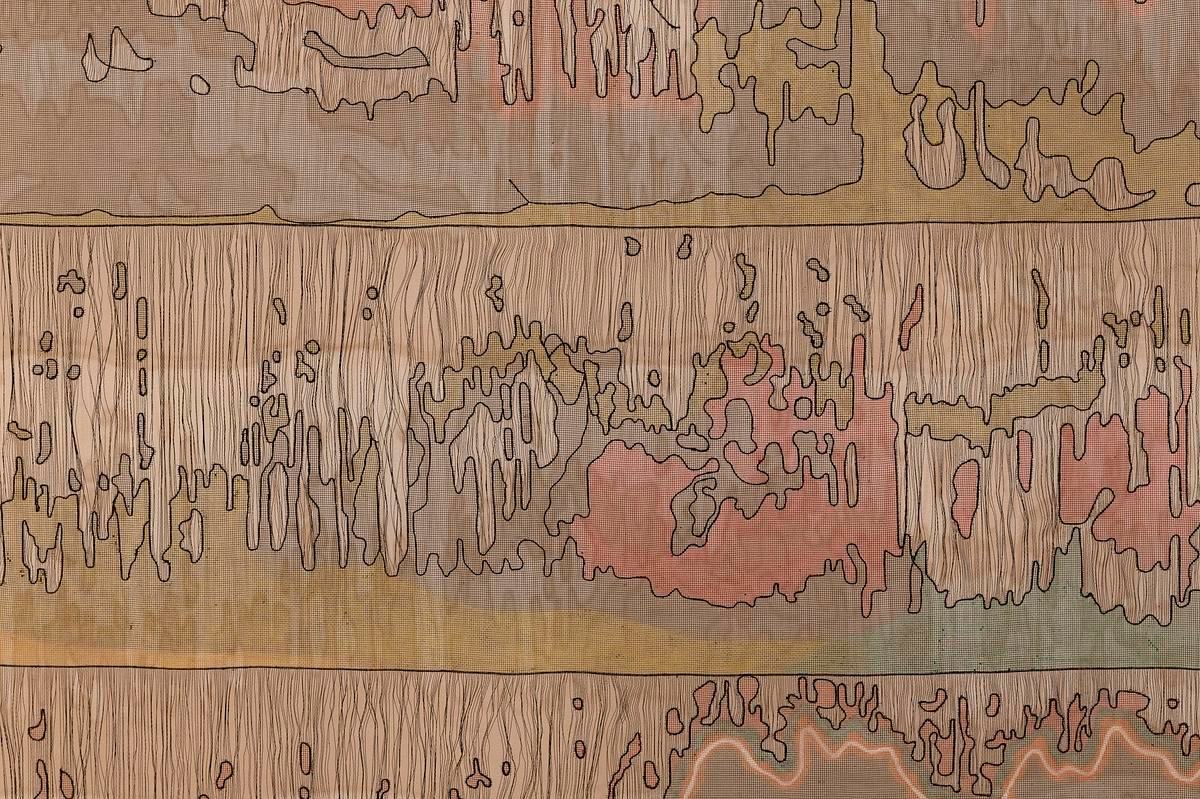

The visual and dramatic climax of the exhibition is the multichannel video installation by Eder Santos, Screen² (2024), an expanded reflection on the very essence of the archive, its fluid boundaries and flexible structure, which can alter depending on external circumstances and creative engagement with it. Showing the limitless possibilities of audiovisual art as a source of knowledge about the world, Santos combines iconic performances of other artists with his own retrospective, the latter consisting mainly of recordings of multimedia stage performances. The soundtrack, written specifically for the installation by Paulo Santos, restructures the poetic statements of the individual works, opening up new relations between them and their layers of meanings and emotions.

1980 | Video, Music and Television. Early experiments with electronic media

In 1985, after twenty years of military dictatorship, Brazil elected its first civilian president, heralding an era of economic and political reforms and opening the way for independent cultural initiatives, including the newly established video festival. It was the brainchild of video researcher Solange Oliveira Farkas initially supported by the well-known photographer and documentary filmmaker Thomaz Farkas, whose company Fotoptica was among the first to bring video equipment to the Brazilian market. The initiative was more than timely: in the 1970s, the artistic community in Brazil had access to very few cameras, among them one was in possession of the Modern Art Museum in Rio de Janeiro and another of the University of São Paulo; in the new decade, video technology suddenly became much more accessible.

Outlining the Festival’s ambitions in its early days, Thomaz Farkas said: “The Soviet cinema invented the cinema eye, and we will introduce the video eye.” Videobrasil quickly became a showcase for artistic endeavours and, together with its artists, set about formulating the vocabulary of the screen culture for the new Brazil.

The works collected in this section show the different sources that contributed to the language of the young art. Avant-garde poetry, television coverage, alternative music, and club culture were no less important for the emerging video art than the handheld cameras and video processing devices which made it technically possible.

There are striking resemblances between Brazilian video art of the end of the dictatorship and Soviet video art of the perestroika era. Tasting freedom for the first time, young artists enthusiastically took up hand-held cameras to shoot video parodies of official television and to make music videos. Interest in the possibilities of new technology and creative deconstruction of the existing video genres united these cultures from different hemispheres. The biggest difference was not in the visual language, but in the setup of production and exhibition. In Brazil, a video camera was an expensive but nevertheless available commodity. In the last years of the Soviet Union, buying a video camera (like many other things) was more like an adventure, where the outcome depended on many factors, from the availability of the right model to the willingness or unwillingness of the seller to deal with a particular buyer.

Another important difference was that in Brazil, independent cultural events such as Videobrasil could happen in public even before 1985, although they were under the watchful eye of censorship. In the USSR, by contrast, video art and contemporary art in general avoided public space until the late 1980s. They existed in private spaces such as flats or squats, and access was controlled by the artists themselves.

1990 | Image and Action. Handheld cameras, mass media, and endless broadcasting

The last decade of the twentieth century saw a revolution in technology as handheld cameras, new TV formats, and the Internet transformed the media landscape. Any event anywhere on the planet could now be captured on video and instantly circulated around the world. Live news coverage and broadcasts of cultural events became commonplace.

The Videobrasil programme of the 1990s reflected this revolution in a plethora of works inspired by new technologies and their artistic lexicon. Authors explored the possibilities of real-time editing combined with live performance. Hybrid works merging music, performance, and real-time image manipulation (VJing) became one of Festival’s trademarks and had a major impact on the Brazilian music scene.

Immersive video installations created in collaboration with the audience became possible as Videobrasil explored new venues—museums, exhibition halls, and other cultural spaces. The geographical reach of the Festival expanded as curators of the main project invited artists from the rest of Latin America, Middle East, Asia, Australia, and Eastern Europe—the so called GeopoliticalSouth—to take part on top of organising large-scale retrospectives of video art classics such as Bill Viola and Nam June Paik.

2000 | Flows, Mergers, Convergences. Dialogue with the South and video as an international language

The late 1990s and early 2000s saw a turn towards digital image production and online distribution. The computer became the primary tool for creating and experiencing video content, and a visual culture specific to the Internet came into being. Computers and the World Wide Web created new hope for a technology-based renewal of artistic language, making available amazing new video effects.

At the same time, many artists espoused a counter-current, seeking to transform video from a code that is transmitted directly to the retina into a bodily experience. The resulting experiments with live performance, the materiality of film, and found images as well as alternative means of producing and distributing video remain relevant to this day. Digital formats brought experimental cinema, contemporary art, and amateur filmmaking much closer to one another, so that new answers were needed to the fundamental questions of the essence of video art, the criteria for aesthetic evaluation, and the institutional framework of the art scene. The old-new problems of authorship and collectivity, elitism and democracy, documentary and fiction came to the fore in Brazil, Russia, and elsewhere. Videobrasil deliberately focused on countries which, like Brazil itself, had remained outside the purview of big institutions and mainstream productions, finding interlocutors there and inviting them to tell their stories.

2010–2020 | The Energy of Imagination. Poetic reconstructions, memory and reinvention of the future

In the 2010s, video became a fully fledged language of self-expression, social critique, and political statements. An endless stream of video content: everyday experiences and artistic gestures, reactions to current events and reflections on traumatic past, imaginary universes, and utopian fantasies have added a new dimension to our reality. Accessible AI, virtual reality, image and text generators led to a fundamental change in the nature of art itself. Technologies are gaining agency, transforming from tools in the hands of artists to equal participants in the creative process. Communities of all kinds (ethnocultural, social, professional) are using video to tell their stories and make sense of them. Archival materials are being integrated into digital universes, and the boundary between fiction and documentary in on-screen storytelling is increasingly blurred. Narrating the self—one’s identity, sociocultural and ethnic origins—becomes a crucial artistic strategy that allows any minority to participate in the creation of a universal social history.

All photos: Daniel Annenkov

Artists

Marina Abs — Victor Alimpiev — Ar Detroy — Dmitry Bulnygin — Calderón & Piñeros (La Decanatura) — Guillermo Casanova — Vitória Cribb — Victor Davydov — Bakary Diallo — Otávio Donasci — Eletroagentes — Ludmila Gorlova — Cao Guimarães — Diana Kapizova — Sandra Kogut — Elena Kovylina — Marcellvs L. — Wagner Morales — Alfredo Nagib — Paulo Nazareth — Rivane Neuenschwander — Timur Novikov — Armando Queiroz — Gia Rigvava — Luiz Roque — Eder Santos — Sergei Shutov — Walter Silveira — Natalia Skobeeva — TVDO — Pedro Vieira — Ezra Wube

Screen² by Eder Santos

Music

Paulo Santos

Artists

Lenora de Barros — Josefina Cerqueira — Eduardo Climachauska — Otávio Donasci — Paula Garcia — Ayrson Heráclito — Dan Halter — Luciana Magno — Emo de Medeiros — Gustavo Moura — Rosana Paulino — Ana Pi — Letícia Ramos — Nuno Ramos — Eder Santos — Paulo Santos — Walter Silveira — Melati Suryodarmo

Curators

Solange Oliveira Farkas, Alessandra Bergamaschi

Co-curators

Dmitry Belkin, Andrei Vasilenko

Assistant curator

Rudá Babau

Architecture

sashakim.studio (Sasha Kim, Ira Ten)

Light

Ksenia Kosaya

Research

Régis Alves, Alessandra Bergamaschi, Marcos Grinspum Ferraz, Eduardo de Jesus, Fábio Kawano

Producers

Varvara Arkhipova, Sasha Chistova, Ksenia Makshantseva

Art logistics and registration

Daria Krivtsova, Daria Pankevich

Technical team

Andrey Belov, Artem Kanifatov, Ksenia Kosaya, Nikita Tolkachev

Accessibility and inclusion team

Aleksandra Kharchenko, Vlad Kolesnikov, Victoria Kuzmina, Varya Merenkova, Vera Zamyslova

Videobrasil communication coordinator

Giulia Garcia

Media specialist

Katya Kiseleva

Associação Cultural Videobrasil

Director’s assistant

Carina Teixeira

Artistic direction

Solange Oliveira Farkas

Archive

Régis Alves

Production coordinator

Carla Souza Poppovic

Financial coordinator

Karine Leves

Legal advisor

Olivieri Associados

The exhibition is organised in collaboration with

Timur Novikov Estate, Saint Petersburg

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

OVCHARENKO

XL Gallery

Videobrasil would like to thank

Tom Butcher Cury, Júlia Contreiras, Fabio Cypriano, Marco Del Fiol, Pedro Farkas, Thomaz Farkas, Van Fresnot, Jorge La Ferla, Ruyi Luduvice, Horrana de Kássia Santoz, Arlindo Machado, Teté Martinho, Danilo Miranda, Vivian Ostrovsky, Ana Pato, Gabriel Priolli Neto, and all the artists, critics, curators, and producers who participated in the Videobrasil trajectory.

- Workshop studioVideo Art: Overload and a Bit More[ Ru ]8–

9 Feb 2025  Public programmeVideobrasil. Needs No Translation. Mediation with Guest Experts[ Ru ]14 Dec 2024–

Public programmeVideobrasil. Needs No Translation. Mediation with Guest Experts[ Ru ]14 Dec 2024–9 Feb 2025  Mediated tourVideobrasil. Needs no Translation[ Ru ]12 Dec 2024–

Mediated tourVideobrasil. Needs no Translation[ Ru ]12 Dec 2024–9 Feb 2025  Mediated tourThe Life of Remarkable Bugs. Part Two[ Ru ]4–

Mediated tourThe Life of Remarkable Bugs. Part Two[ Ru ]4–8 Feb 2025 - Film programmeVideobrasil. Resistance and Struggle[ Ru ]25–

29 Jan 2025 - PublicationEverybody's a Director (And an Artist). Solange Oliveira Farkas on Video Art

Book collectionIn Original Language. Published by Videobrasil[ Ru ]from

Book collectionIn Original Language. Published by Videobrasil[ Ru ]from20 Jan 2025  Reading groupVideo Essay: Films Beget Films[ Ru ]12–

Reading groupVideo Essay: Films Beget Films[ Ru ]12–26 Dec 2024  Book collectionVideobrasil. Needs No Translationfrom

Book collectionVideobrasil. Needs No Translationfrom12 Dec 2024