The first complete retrospective in Russia of the founder of Brazilian “Cinema Novo” and one of the most brilliant filmmakers of the twentieth century.

The first complete retrospective in Russia of the founder of Brazilian “Cinema Novo” and one of the most brilliant filmmakers of the twentieth century.

"The late 1960s were a crazy time. Every two or three days a film came out in cinemas that you wanted to call a masterpiece. But Antônio das Mortes eclipsed them all. I still return to it often—and often show it to friends. But only if they deserve it!"—this is how Martin Scorsese confessed his love for one of Glauber Rocha’s films. An introduction to Rocha, the titan of Brazilian Cinema Novo movement, its most influential and most outspoken director, could easily consist of a chaotic, passionate, excessive montage of quotations, words spoken about him by other giants of cinema and by Rocha himself. Such an approach would, in a way, resemble his films: uncompromising, exalted, polyphonic, and polemical to the extreme.

Wherever there is a filmmaker, of any age or background, ready to place his cinema and his profession at the service of the great causes of his time, there will be the living spirit of Cinema Novo.

— Glauber Rocha, The Aesthetics of Hunger

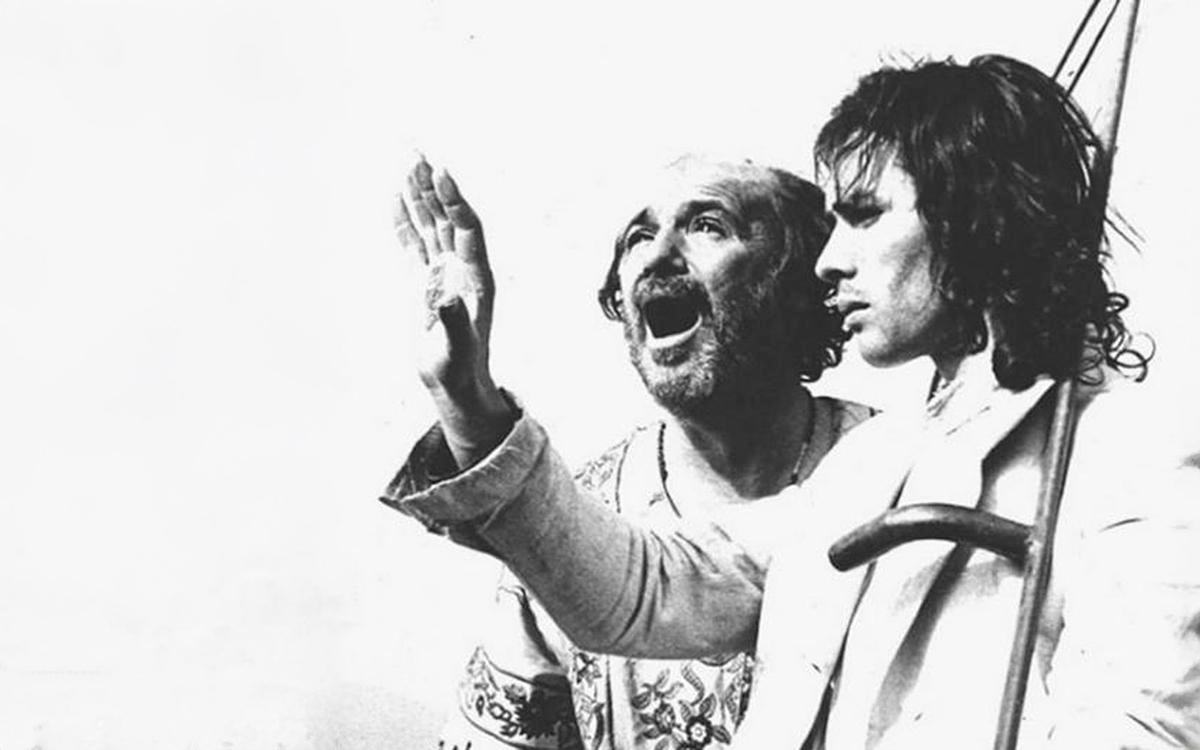

Antonioni wrote that in Rocha’s films, “every scene is a lesson in what modern cinema should be.” Bertolucci considered him a friend and an equal. Buñuel called his films “the most beautiful that I have seen in ten years.” Critic Serge Daney proclaimed him “one of the great tricksters of our time.” Perhaps the most comprehensive expression of admiration came from Godard, who in Wind from the East (1970) cast the Brazilian as the final boss of revolutionary cinema—a symbol and guiding figure, arms raised to the sky.

But let us also give the floor to Glauber Rocha himself: “New cinema—that is me.” New cinema is, of course, cinema novo: a group of closely collaborating Brazilian filmmakers of the 1960s, and a national cinematic phenomenon that followed the French New Wave and took the world by storm. Yet cinema novo is also new cinema in a broader sense—as a principle, a necessity, an idea. An idea of which Rocha was one of the most vivid and striking embodiments. In fact, he was the one who proclaimed it, articulated it, and laid out its demands. First within a national context, in his book Critical Review of Brazilian Cinema (1963), which provided the ideological foundation for the rise of cinema novo and called for the birth of an innovative cinematic language capable of reflecting the specific social, political, and cultural realities of early-1960s Brazil. And later, one that cast an angry gaze over the entire world hungry for change.

In 1965, Rocha’s manifesto The Aesthetics of Hunger exploded onto the world of auteur cinema like a bombshell. Film was rapidly becoming politicised, and Rocha provided that process with a system of coordinates—clear, coherent, and genuinely visionary. At just twenty-five, he called not merely for the depiction of the relentless hunger endured by the cursed inhabitants of the so-called Third World, but for its inscription at the formal and structural level of film itself: to transform violence—"the noblest cultural manifestation of hunger and the only means by which the colonised can force the colonisers to acknowledge their existence“—into “the violence of cinematic images and sounds.”

Revolutionary art should be a powerful enough magic to enchant man beyond the point where he can no longer keep on living under this absurd reality.

— Glauber Rocha, The Aesthetics of Dreaming

No one questioned the young director’s right to proclaim new horizons for cinema. A year before The Aesthetics of Hunger, Rocha’s second feature, Black God, White Devil (Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol), caused a sensation at Cannes. The Brazilian’s subsequent films—the political thriller Entranced Earth (1967), merciless toward both left and right, elites and intelligentsia alike, and Antonio das Mortes (O Dragão da Maldade contra o Santo Guerreiro, 1969), which developed the ideas and symbolic language of Black God, White Devil—brought him Cannes nominations and awards, as well as recognition as one of the most original and significant filmmakers of his era.

Meanwhile, Brazil’s military dictatorship tightened its grip. Entranced Earth was temporarily banned, Rocha’s criticism of the authorities led to his arrest (fortunately brief), and in 1969, like many of his contemporaries, he left the country, spending seven long years in exile. Exile did not dampen his fervour; it radicalized his experiments. Rocha refused to repeat himself and continued to reinvent cinema with each new work, culminating in 1980 with the cosmological scope and global ambition of The Age of the Earth.

After contracting a severe lung infection, the director died a year later, at forty-two, having largely lost his audience. The enthusiasm and struggle of the 1960s, when Rocha’s films struck the exposed nerve of a restless era, gave way to disappointment and moral crisis. His works of the 1970s—Cutting Heads and The Lion Has Seven Heads (1970), Claro! (1975), and later The Age of the Earth—were misunderstood and, for the most part, scarcely seen. To many contemporaries, the Brazilian’s passion, pathos, and radicalism came to seem out of place.

Yet as early as 1971, Rocha had already replaced the Aesthetics of Hunger with the Aesthetics of Dreams. His second programmatic manifesto located revolutionary potential no longer in violence, but in the liberation of the subconscious: in a Borges-like dream logic of art, in an unbounded surrealism that knew no limits. And if in the 1970s it seemed to many that Rocha had fallen out of step with his time, half a century later it is clear that he had simply outrun it—in his own words, he was making films not for the present, but “for the audiences of the future.”

That future has arrived. And the dizzying, avant-garde march of images and symbols that characterized Rocha’s cinema, in an era of informational overload, now appears as a mirror capable of revealing the sharpest contradictions and illusions of the present. The personal revolt of the Brazilian genius continues—and will remain necessary for a long time to come.