From 1930s futurism to 2020s fatalism: Ten jaw-dropping images of the future in iconic sci-fi films.

From 1930s futurism to 2020s fatalism: Ten jaw-dropping images of the future in iconic sci-fi films.

A lone wounded girl makes her way cross an abandoned city, tracked by military patrols, forgetful of her own name and of what caused the collapse of civilization around her. A brother and sister—he in a wheelchair, she half-crazed—seek in vain for a way out of a pitiless post-apocalyptic wasteland. A husband and wife are tragically alienated by the pressures of a society that is caste-based and regimented to the detriment of feelings. Cities burn. Machines rebel. The desperate survivors pay no attention the now worthless scraps of a former civilization—our civilization—which are blown away by the wind.

Illustration: Stepan Lipatov, Varya Fomichev

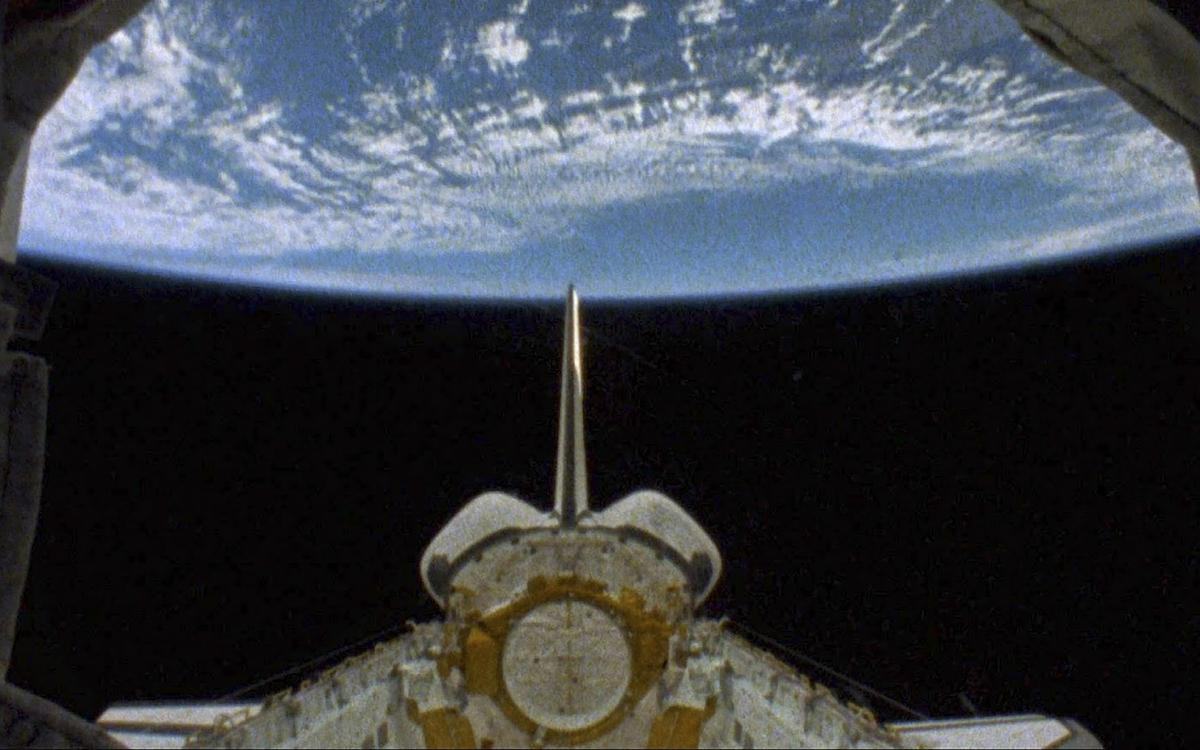

To say that these extracts from cult science-fiction films do not radiate optimism is to put it mildly. What became of the hopes and dreams of the industrial age and the dawn of the space age? Cinema, more than any other art form, is geared to the production of incredible dreams. Why, then, does the utopian impulse almost always lose out to images of dystopia? Why are the future-oriented fantasies of directors and screenwriters so often dominated not by better, more just and progressive models of society and the world order, but by apocalyptic warnings and disturbing visions of permanent crisis?

Fredric Jameson, a contemporary thinker who has engaged extensively and seriously with the themes of utopia and science-fiction, believed that these questions come from the wrong angle. The true and essential quality of sci-fi is not its ability to imagine the future, but, on the contrary, its ability to bear witness, time and again, to the impossibility of imagining the future. Sci-fi demonstrates, lucidly and compellingly, the limitations of the imaginative capacities of human beings.

But even if that is so and even if much sci-fi is in the nature of low-brow entertainment (witness the vast majority of American and contemporary Russian sci-fi films, usually served up with a large dose of ideology), the genre can offer directors of auteur cinema a valuable space to express their ideas.

In the hands of the right director futuristic pessimism can cease to be ideologised. Instead of being an expression of paranoid alarm at humanity’s regression or at the dominance of imagined totalitarian societies, as in Hollywood dystopias, it can stretch the limits of collective imagination and probe the boundaries where the dream of a better future encounters systemic, cultural, and ideological barriers that prevent the dream from taking on a truly radical and new form.

The film programme The Sunset Fired a Hundred Suns dialogues with the same-name exhibition at

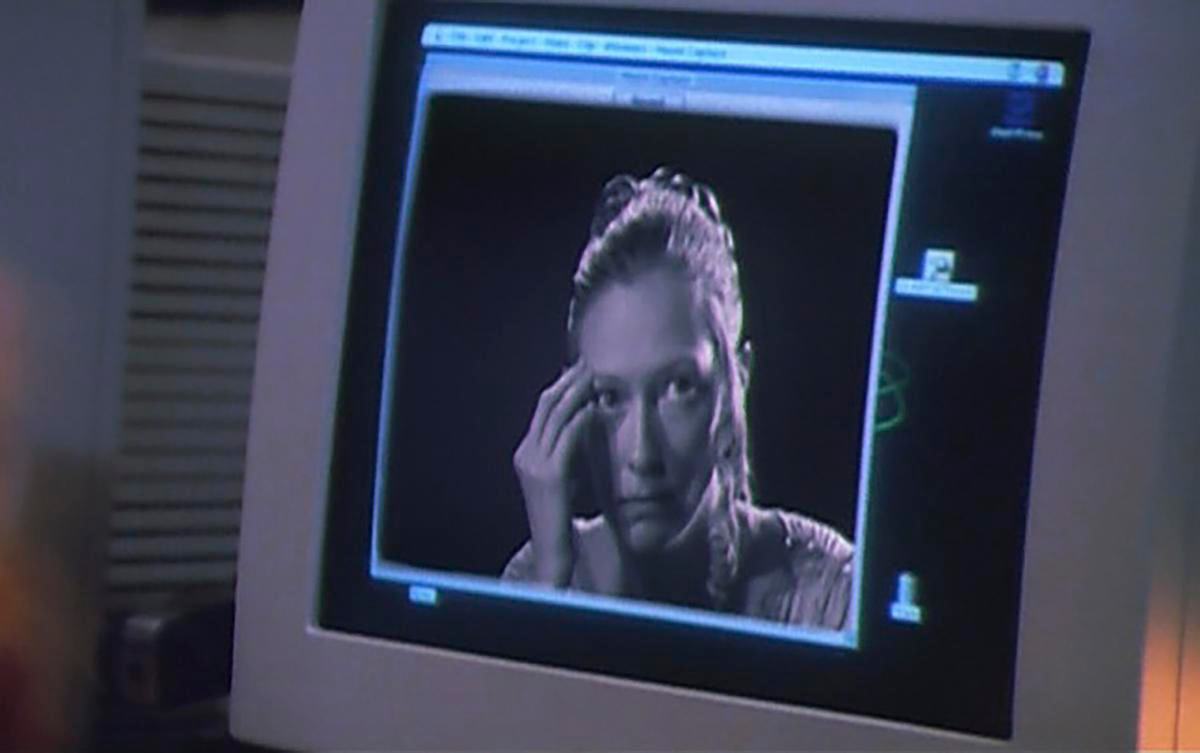

The cycle includes works by New German Cinema classics, Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Werner Herzog (their only ventures into sci-fi), as well as the new Brazilian festival hit Dry Ground Burning, which achieves an anti-utopian effect through semi-documentary cinema. Soviet sci-fi of the 1930s, bristling at future threats from artificial intelligence, rubs shoulders with a math-based fantasy about the potentials of virtual reality, personified by a young Tilda Swinton. Cult Greek sci-fi from the 1980s, evoking memories of dictatorship, is juxtaposed with an Ethiopian dystopia unfolding in the space of memory of a vanished twentieth-century pop culture.

Ultimately, even if a fantasy utopia is doomed to be a testament to its unreality, a cinematic utopia is quite possible. The Sunset Fired a Hundred Suns brings together a clutch of films, all truly unique and pushing the genre boundaries of cinematography in contexts and realities that might not seem conducive to such innovation.