The new life of personal documentary filmmaking is revealed in the latest film programme at

The new life of personal documentary filmmaking is revealed in the latest film programme at

What happens to the documentary when its director crosses the invisible line between the off-screen and on-screen space—and becomes not only the author and narrator but also the hero of their own film? For the first half-century of cinema history, this move was considered unthinkable: documentary filmmaking, while inevitably deceptive, tried to present itself to the audience as neutral, aspiring to create an objective picture of the world.

Subjectivity gradually began to enter non-fiction cinema shortly after the Second World War: visual images of the war presented facts but did not convey what people had experienced. It was at this moment that directors dared to speak from the first person, initially in experimental film, establishing a genre that became known as personal documentary. Jonas Mekas and Jean-Luc Godard, Agnès Varda and Chantal Akerman, Kazuo Hara and Stan Brakhage—in the second half of the twentieth century, each of them expanded the boundaries of the new genre in their own way, putting themselves into their films.

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, personal non-fiction had gained increasing legitimacy as the authority of factual documentaries waned. Starting from the 2010s, the most popular genre of experimental documentary features directors putting themselves in their films. No film festival or discussion of contemporary cinema is complete without such works.

Along with the intensive rethinking of the nature of film as a document and the debunking of its classic dichotomy between subject and object, it is precisely in non-fiction cinema that the most diverse forms of expression have developed recently. Self-portrait and autobiography, autofiction and film essay, home videos and home ethnographic studies, diary films and performative documentaries—all these subgenres of personal cinema entail a different modality of directorial presence, where directors work with themselves and their own experience.

At its best, personal cinema also contains true revolutionary potential: it transforms documentary filmmaking itself, whose canons mutate as the familiar dividing lines are blurred (objectivity/subjectivity, fact/experience, author/hero), as well as the concept of authorship itself. The American art critic Peter Schjeldahl once wrote that “authors are not the causes, they are effects of the language they use.” These words not only apply to documentary cinema, but it seems that we can see the formation of the author most clearly in non-fiction films with a first-person perspective, as directors try to find themselves in contact with the medium of cinema.

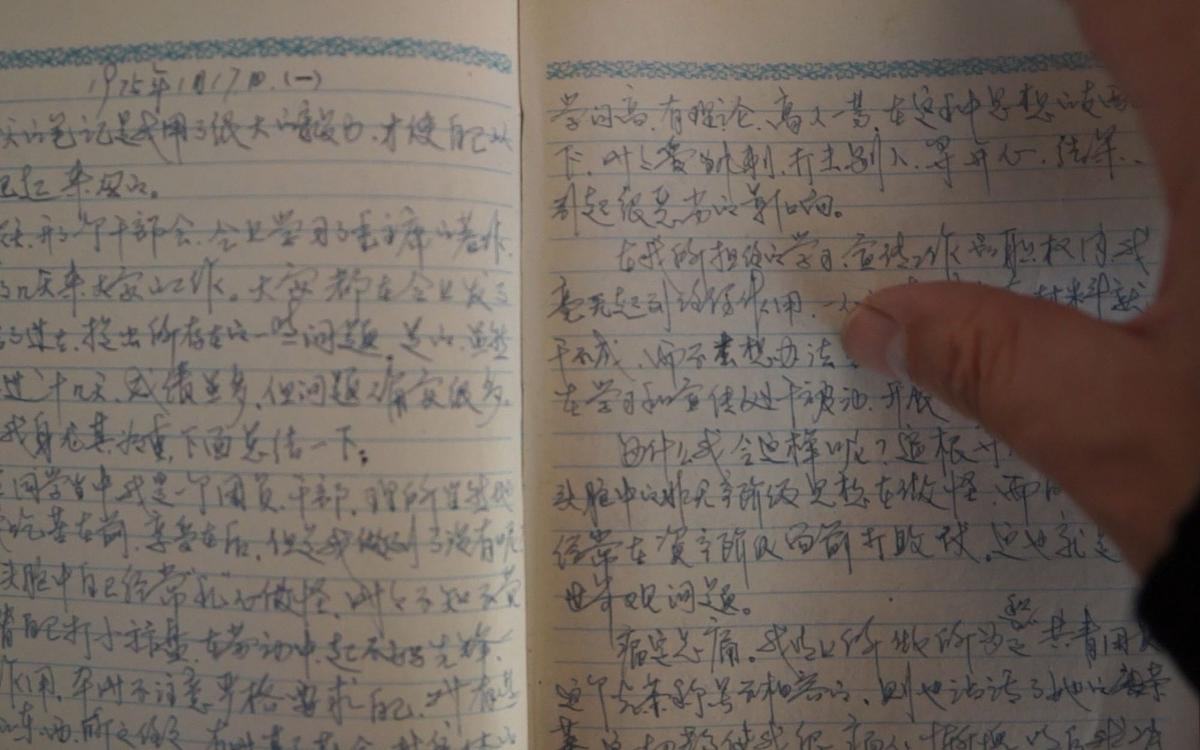

Family Album presents viewers with some of the most captivating and astonishing examples of how directors in the last decade and a half have been reinventing themselves using the movie camera. Some directors turn to cinema to transform their own traumatic experiences into a map of the illnesses of society as a whole, such as Shiori Ito, a journalist who was raped by a friend of the Japanese Prime Minister and made Black Box Diaries about her investigation of the crime. Others, like Rosine Mbakam from Belgium and Zhang Mengqi from China (in a series of 11 films!), focus on their families’ biographies and places of residence, to capture the worlds that shaped the directors themselves, and which they find increasingly remote.

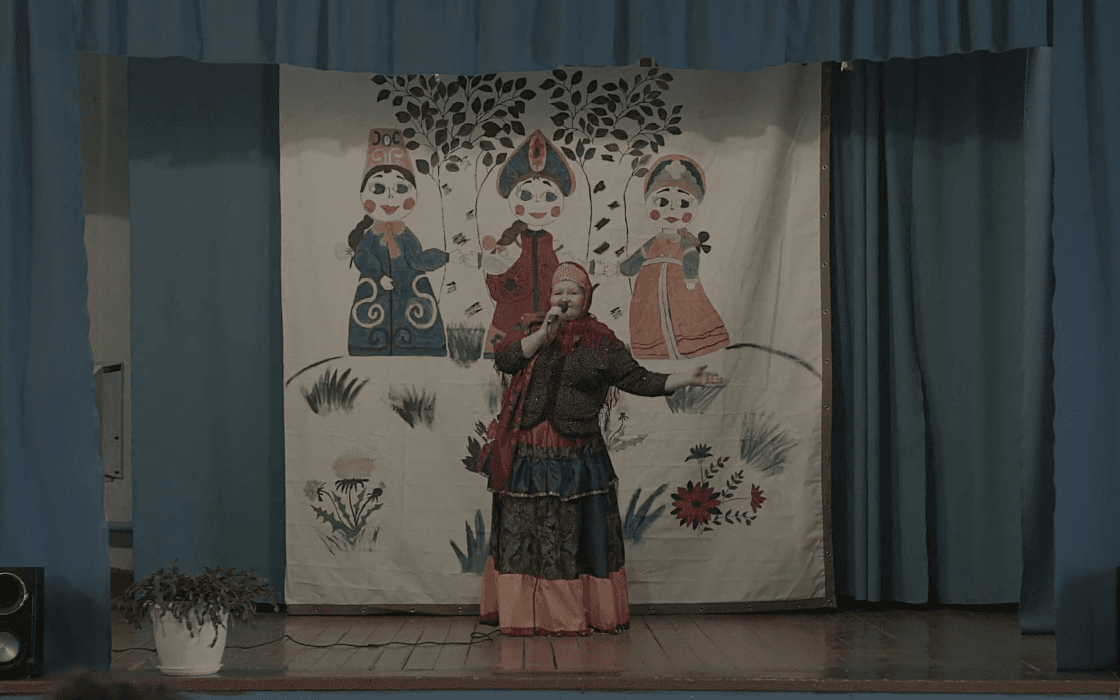

For Andrés Di Tella and Manuel Embalsé from Argentina, personal documentary becomes a means of travelling into the cultural past and digital future respectively. The great Chinese documentarian Wu Wenguang, who gained renown for his films about the Cultural Revolution and the Tiananmen Square protests, now gradually discovers himself through the diverse interactions that have defined his current worldview, from the mother who raised him to participants in his workshops. In their turn, Russian filmmakers from different generations, Andrey Silvestrov and Dasha Likhaya, cannot resist establishing their own relationships with the social and cultural landscape surrounding them, using devious performative practices: for Silvestrov, Russia seems like a collective dream, while Likhaya presents it as a personal, almost intimate fragment of memory.