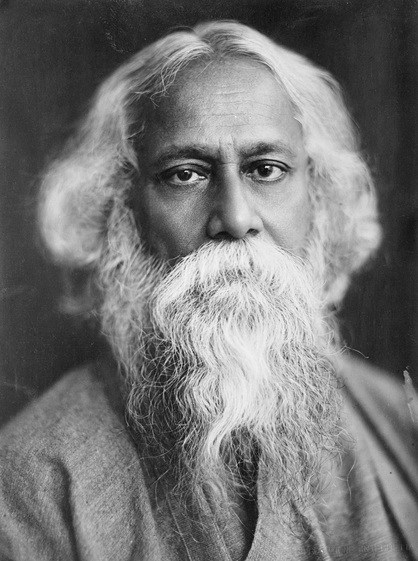

The story of the life and creative searches of one of the most influential Indian thinkers of the twentieth century.

Rabindranath Tagore: a Biography

- Age:

- Type:

- Age restrictions

- 12+

Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) came from a wealthy and influential Bengali family of landowners and reformers, where Hindu, Muslim, and European traditions were equally respected. Raised with ideals of openness towards the world and towards all kinds of knowledge, Tagore learned to view the collision of different outlooks not as a threat, but as a source of strength. The future poet grew up in a home where art and spirituality were a natural part of everyday life. He realised from a young age that education was not just about lessons and books: much could also be learned from gardens, from music, and from conversation with other people.

Bettmann Archive

Tagore spent his youth in spiritual searches and travels between East and West. He was sent to study in England. However, it was not so much English university education as the encounter with a different culture, which had the biggest impact on the young man. Tagore returned to Bengal without completing his studies and devoted the next decade to literature and music. Later, the task of managing the family estate gave him an intimate understanding of the life of the Indian peasantry—their poverty, the rhythm of their labour, and their potential for harmonious community living. By encountering a different culture and then immersing himself in his own, Tagore reached the conclusion that no tradition has a monopoly on truth and that a person can only be truly free by remaining receptive and open to a multitude of different voices.

In his mature years, Tagore made his name not only as a poet and writer, but also as an artist, philosopher, teacher, and composer. He published over fifty collections of poetry, including Gitanjali (“Sacred Songs”), which won Tagore the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913, making him the first Indian writer to achieve international fame. His novels, plays, and short stories, exploring issues of identity, tradition, and modernisation, created new forms in Indian literature and are acknowledged classics of the Bengali Renaissance. Tagore’s paintings are remarkable for their unique visual language. For Tagore, art was never merely decorative: like education, it was inextricably linked to social processes and to life itself.

Rabindranath Tagore. Untitled (“Large Geometric Figure with Two Prostrate Figures”), 1928

The university which Tagore created in Santiniketan, a district in his home region of West Bengal, occupies a special place in his legacy. From its beginnings as a school in 1901, the institution developed under Tagore’s guidance and became Vishva-Bharati University in 1921. The Sanskrit motto of the institution was Yatra visvam bhavatyekanidam (“Where the whole world finds a home in one nest”). It has been borrowed as the title for the exhibition at

Learning at Vishva-Bharati University was not limited to books: students mastered the handling of natural materials, studied traditional crafts, and took part in agricultural work. Art was a part of their everyday life, and the learning environment combined nature with culture and personal freedom with social responsibility.

Tagore’s life was in constant motion. In 1912, he again visited England where he made Gitanjali known to a broader audience. In 1916–1917, he lectured in Japan and the United States, and subsequently travelled throughout Europe, meeting along the way with Romain Rolland, Albert Einstein, and Bernard Shaw. In 1930, Tagore visited the USSR, where he praised the new education system but also called attention to alarming signs of the suppression of freedom. For Tagore, each journey to a foreign country was not only a cultural mission, but also a lesson in another culture, an opportunity to hear its unique voice. Tagore’s ideal was a world that “has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls” (Gitanjali: 35) and where the values of different peoples do not exclude but complement each other.

Tagore also played an important role in the twentieth-century history of India. He backed the anti-colonial movement but did not support the use of violence, believing that true independence sprang from spiritual and cultural liberation. He maintained a friendship and debate with Mahatma Gandhi that spanned many years: they respected each other but disagreed on certain points—Tagore criticised Gandhi’s policy of non-cooperation and argued that India should be open to the world, rather than closed off in its own traditions. For Tagore, social activism was a continuation of his educational and creative work: he avoided slogans and sought to create conditions whereby each person could find dignity and freedom.

In the last decades of his life, Tagore spoke with increasing urgency of a crisis in civilisation, offering an original view on the specifically twentieth-century problems that preoccupied philosophers and other thinkers. For Tagore, the crisis was not so much that of a confrontation between nations or ideologies as a rift between man and machine, human personality and organisation, culture and the inhuman logic of power. Progress, for Tagore, is measured not by the invention of new devices to make daily life more convenient, but by the growth of the human personality. His call for humane development remains one of his most relevant legacies today.