The soundscapes of Renaissance Paris and London meet with a classic of the twentieth-century avant-garde in the final concert of the Music (Hi)stories series.

The Cries of London. Intrada, Ekaterina Antonenko, Yaroslav Timofeev

- Date:

- 24 Jun 2025,

20:00–21:30

- Age restrictions

- 12+

Programme

Orlando Gibbons (1583–1625)

The Cries of London I, ca. 1610

The Cries of London II, ca. 1610

Henry Purcell (1659–1695)

Fantasia Upon One Note, ca. 1680

Thomas Weelkes (1576(?)—1623)

The Cries of London, ca. 1610

William Cranford (?—1645)

Fantasia, before 1641

Luciano Berio (1925–2003)

Cries of London, 1974–1976

According to sociologist Howard Becker, the birth of a work of art requires a combination of interacting agents and social relations. Just such a combination is to be heard in the choral work, The Cries of London, by Orlando Gibbons (1583–1625), where the protagonists compete to sell fresh oysters, mutton pies, and ripe pomegranates to passers-by, ask for news of a lame grey mare gone missing, or offer to deal with mice infestations and corns. In his music the master composer of the English High Renaissance captured the voices of merchants, beggars, coachmen, and hawkers on the streets of early seventeenth-century London, giving to music one of the earliest and most vivid examples of the field-recording genre.

Performed by

Vocal ensemble Intrada

Ekaterina Antonenko conductor

Yaroslav Timofeev concert host

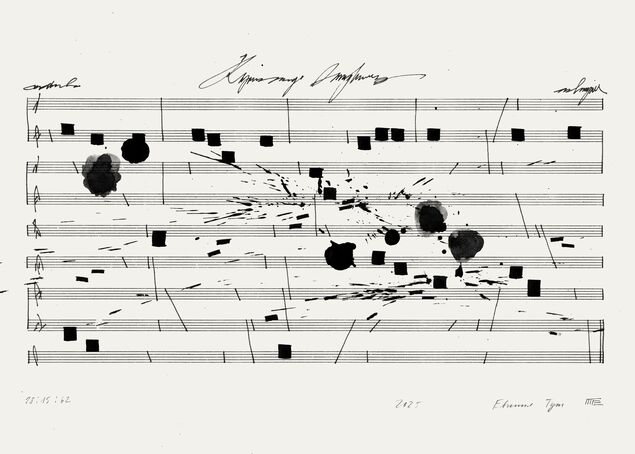

Illustration: Yevgenia Tut

The recording of ambient sounds and creation of musical works is common practice in our time, but it actually goes back even further than Gibbons: in the sixteenth century, the French composer, Clément Janequin, anticipated the Englishman with his Les Cris de Paris (1547). However, it was in Elizabethan and Jacobean England that the conversion of street cries into music became a pet device of composers, with Thomas Weelkes and Richard Dering writing short (seven- to eight-minute) pieces for vocal ensemble and a consort of viols that rival the classic work by Gibbons. They use documentary material to produce a virtuoso polyphonic texture, voices overlapping each other in the manner of a motley street crowd and the change of metre imitating the chaos of the market square. Listeners familiar with the lofty and sophisticated compositional technique of Renaissance sacred music will be struck by its application to such profane subject matter.

In their efforts to convey as accurately as possible the rhythms and intonations of everyday speech, these Renaissance composers anticipated the discoveries of twentieth-century music, and it is no coincidence that the works of Gibbons and his contemporaries enjoyed a new wave of popularity in the 1970s. That is when they attracted the attention of researchers and performers of early music. The post-war avant-garde master Luciano Berio went so far as to write his own Cries of London, entering into dialogue with the Renaissance tradition at a new juncture in the history of music.

The Intrada vocal ensemble was founded in 2006 by Ekaterina Antonenko, a graduate of the Moscow Conservatory. It has taken part in many high-profile projects in Russia and abroad, and has won renown as an exceptionally versatile and professional vocal group. In 2019 and 2021, it was voted Ensemble of the Year by the newspaper Muzikalnoe Obozrenie. Intrada regularly collaborates with leading ensembles and musicians in Russia and abroad, including the Moscow Soloists chamber orchestra and Yuri Bashmet, the Svetlanov Symphony Orchestra and Vladimir Jurowski, the Russian National Orchestra and Mikhail Pletnev, Le Poème Harmonique and Vincent Dumestre, Il Giardino Armonico and Giovanni Antonini, The Tallis Scholars and Peter Phillips, VOCES8, I Fagiolini and Robert Hollingworth, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Frieder Bernius, Stephen Layton, Hans-Christoph Rademann, Peter Neumann, Jean-Christophe Spinosi, and many others. The ensemble has also performed at the “December Nights of Sviatoslav Richter” at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow.