The final “wave” of The Coastline Paradox exhibition invites the viewers to reflect on the peculiarities of culture and science in a permanent risk zone.

Ring of Fire

- Date:

- 17 Dec 2024–

12 Jan 2025

- Age restrictions

- 6+

Living on Kamchatka means being constantly reminded of extreme natural conditions. Eruptions and earthquakes are common here, along with other natural dangers—for example, an attack by wild animals. Most of the peninsula is inaccessible and unsuitable for human life—the small towns and villages swiftly yield to wastelands that stretch for hundreds of kilometres.

Washed by the Bering and Okhotsk Seas, and also the waters of the Pacific Ocean, the peninsula even stands out among other zones of the Pacific Ring of Fire, where up to 90% of all earthquakes and eruptions in the world take place. On Kamchatka, seismic activity is extremely high, and there are more active volcanoes than practically anywhere else on Earth. Unsurprisingly, the risk of encountering natural disasters or mortal danger becomes one of the key subjects for local residents and guests of the region, whether they are artists, writers, researchers, or tourists.

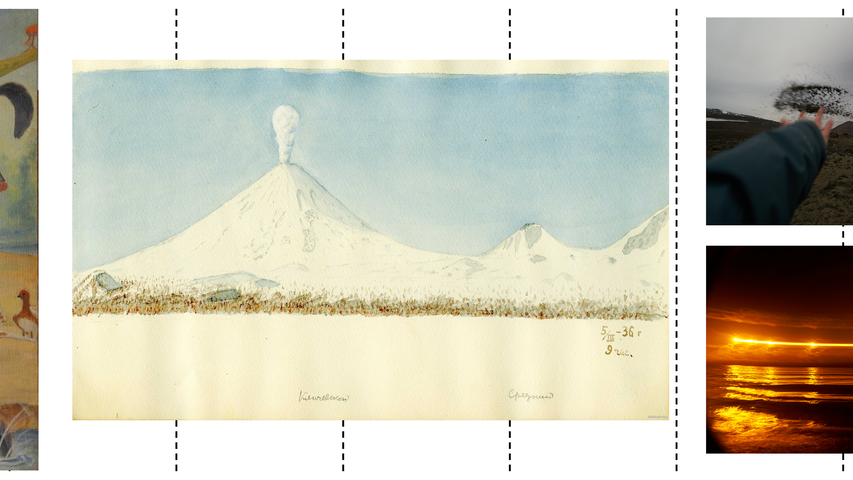

The renowned Koryak writer and artist Kirill Kilpalin, whose self-portrait is displayed at the exhibition, lost an eye when protecting his son from a bear. The image of a bear as a dangerous but at the same time fascinating creature is interesting for guests from the "mainland"—for example, the animal is the subject of a series of drawings by Aleksandr Belashov. Guests are also interested in the battle with the elements: the characters in Dmitry Shakhovskoy’s works are Kamchatka fishermen, who are often forced to work in extreme conditions. Some historical context is also provided with a seventeenth-century engraving by the German polymath Athanasius Kircher, which illustrates concepts about the origin of volcanic activity in those times.

Sometimes, danger on Kamchatka also comes from humans. A case in point is Steller’s sea cow, a large herbivorous sea mammal. It was discovered by scientist Georg Steller during Vitus Bering’s second Kamchatka expedition in the 1740s, but by 1768 it had been driven to extinction. Kamchatka also showed no mercy to Bering himself: the explorer died of scurvy on an island which was subsequently named after him. The exhibition features a model of Bering’s grave and a reconstruction of one half of his face.